The Godfather of Conservation: An exclusive interview with Tony Fitzjohn OBE

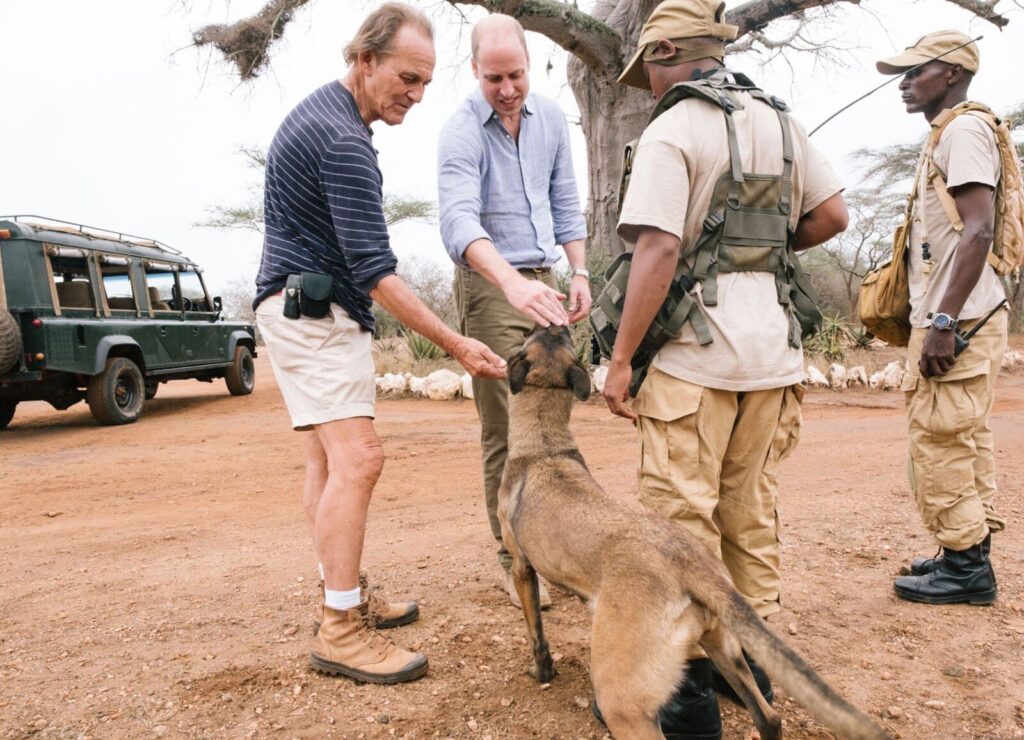

In an exclusive interview, True Travel founder Henry Morley spoke to Tony Fitzjohn OBE, heralded as one of the founding fathers of conservation, about working on the ground to protect the African continent’s most endangered wildlife for over 50 years.

About the Author

As the Founder and CEO, Henry launched True Travel after driving from the north to the south of Africa, working on conservation projects along the way. It became clear that the luxury travel industry needed a fresh approach.

When Tony Fitzjohn was 23 years old, he set off for Africa. Back then, the young Londoner had no plans beyond tracking down an aunt of his (‘the only relation I ever liked’) in Cape Town, but he instinctively knew he was heading in the right direction. ‘I had a childhood dream of running around Africa and playing Tarzan,’ he explains. ‘So I decided, I’m going to go to Africa and live this life I always wanted to lead. I worked as a long-distance truck driver, then ended up hitchhiking through the continent, and got to Kenya. It was everything in my imagination, in my dreams.’

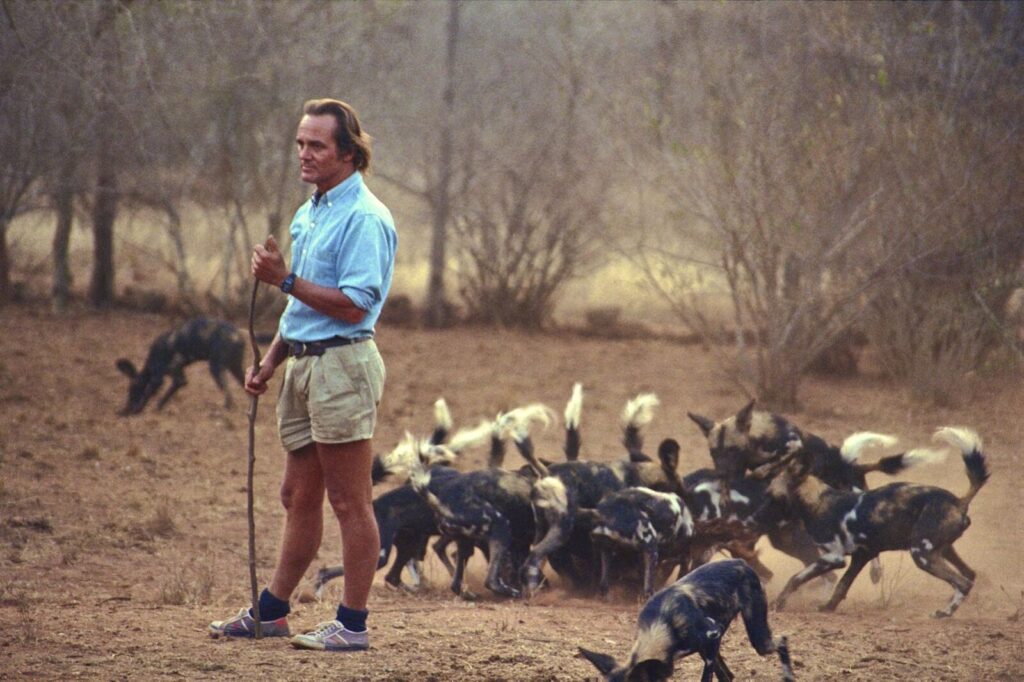

Almost five decades in, Fitzjohn, now 75, is still living in the continent of his dreams. Ever since he pitched up in Kenya in 1971, he has worked rehabilitating animals and reintroducing them back into the wild. He spent 18 years at Kora, a lion camp run by George Adamson, whose wife Joy Adamson wrote Born Free about their experiences, before spending the next 31 years in Tanzania. There he transformed Mkomazi, a derelict game reserve, into a now-thriving national park with two black rhino sanctuaries and a thriving wild dog programme. In 2016 he received an OBE for his hard work and has been the subject of the film To Walk With Lions. It’s no surprise he is often labelled the godfather of conservation.

‘Don’t make a hero out of me,’ he protests when speaking to True Travel. ‘I love it and I can’t do anything else. I think I’ve always done a lot in life because people have always believed in me before I believed in myself.’

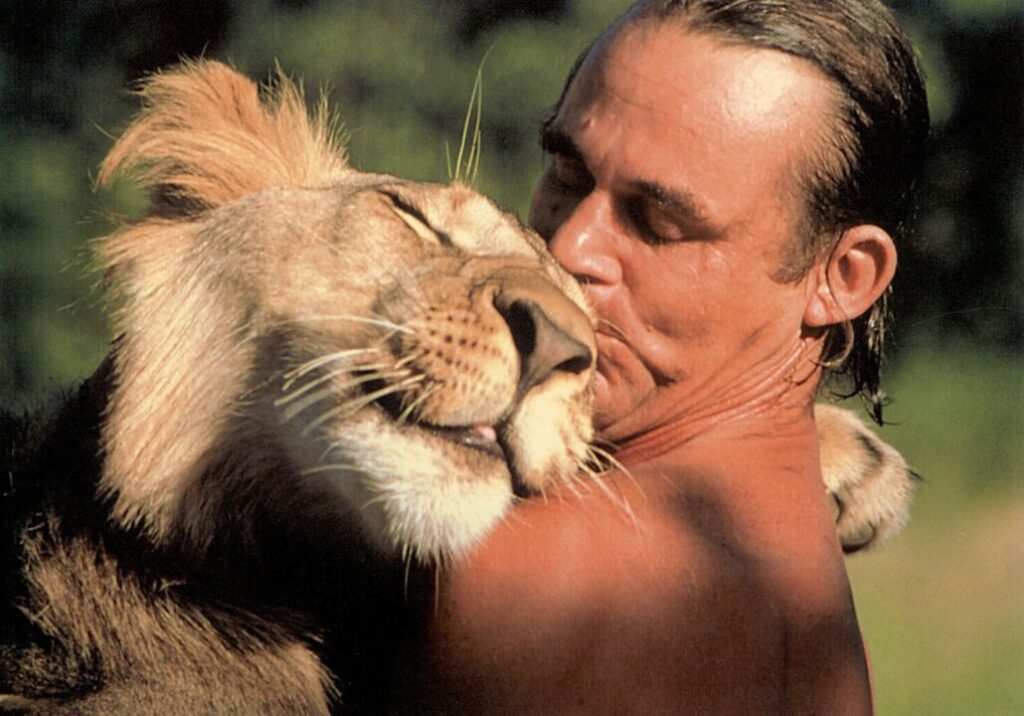

One of those people was George Adamson. Fitzjohn heard through his wife Joy that Adamson was looking for help because his previous assistant has just been killed by a lion. ‘I thought it sounded great; I was full of testosterone and madness.’ After a week at Kora, Adamson asked him how long he thought he’d stay for, assuming he’d stay a few months. Fitzjohn replied, ‘10 or 12 years?’ In the end, he spent 18 years with Adamson, during which time they reintroduced 30 lions and over 10 leopards successfully into the wild, plus their offspring. Their lions were sourced from a range of ranches and zoos, arriving under a year old, where they were gradually guided into the wild. The lions became a part of the family, especially Freddy – a young lion who once saved Fitzjohn’s life when he was attacked by another lion.

Eventually, Freddy left Kora to live free in the wild. Fitzjohn hadn’t seen him in a year when he suddenly came across him calling out in the bush. ‘This weird feeling came over me,’ he recounts. ‘I thought, do I get out and call him? He’s been alone for a year, he’s out of trouble and alive. In that moment I decided, no we drive on. I didn’t want to interfere with his life and what he’d become and drag him back into the horrible world of humans. It was the hardest decision I’d made in my life. I’d never been closer to anybody in my life like I was with Freddy.’

Those years at Kora taught Fitzjohn everything he needed to know to become the internationally renowned conservationist he is today. ‘I grew up there with this lion Christian who’d come from England,’ he laughs. ‘Christian was bought in Harrods, raised in the King’s Road, and came out with a fanfare. He was two. He had no idea what was going on, and I knew nothing. Between George and Christian, I learnt a lot of what there was to know about lions, the bush, and how to see the bush through the eyes of the animals rather than humans.’ Adamson was tragically murdered in 1989, aged 83, when he tried to rescue his assistant and a tourist from Somali bandits. It’s something Fitzjohn still carries with him. ‘It still gnaws away at me but there was nothing I could have done. He went out like a charging lion. I hope I go like that. But what George would have preferred was that the work went on.’

‘It wasn’t easy. ‘To this day I don’t know how I found the money to do it; I made the whole of Mkomazi with a gifted JCB digger,’ says Fitzjohn. He tells a moment when he stood there crying, feeling he’d never finish the infrastructure work he needed before he could even start preserving the wildlife: ‘I thought, I don’t know what I’m doing. Then I thought about George and him saying do things one step at a time. So I did. It’s just work, and I am good at it.’

He decided to focus on working with wild dogs, after initially planning on work with cheetah and then realising there was already a healthy cheetah population. ‘Wild dogs are a pack animal,’ he explains. ‘When you put them into the wild, you just have to hop you’ve done the right thing, that their own instincts and inherited knowledge will take over. That proved to be the case. Most of the dogs went back very successfully. But they need thousands of square miles to roam. Sadly, I think in my future they won’t be able to roam free like they did many years ago.’

The other focus at Mkomazi was the rhino. ‘I knew if Mkomazi was going to survive we had to get it out of the reserve status and into national park status, and we needed an iconic species to do that. I thought the rhino would obviously be the animal to do that.’ In 1989, when Fitzjohn arrived at Mkomazi, there were two dozen rhinos in Tanzania. A decade earlier, there’d been 10,000. While a 1970 count showed a rhino in every square mile at Mkomazi, with every female having a calf. ‘But when I arrived, there wasn’t a single rhino,’ says Fitzjohn grimly.

With the help of friends, he created a plan to buy rhinos from national parks and foreign zoos, creating highly-fenced sanctuaries, and guardian them day and night until the world regained its sanity and allowed rhinos to live.

As the operation grew to greater success, Fitzjohn and his wife founded an education project. They helped build 40 local schools, as well as creating their own secondary school. ‘If you’re going to survive, you’ve got to get your neighbours on the side,’ explains Fitzjohn pragmatically. ‘Education for their kids was what they wanted most so that’s what we did.’

‘I realised that what my job entailed wasn’t to carve out a piece of Africa for myself in someone else’s country and say look at me, I’m the king of the castle. My job was to train Tanzanians to do this job. Ultimately if these animals are to survive, they have to accept the responsibility and have the feelings to want to do it for themselves. I could not cling on to it forever. I had to pass it on.’

This year Fitzjohn is officially moving on from Mkomazi. He has handed the whole operation over to Tanzania National Parks, in whom he has full faith it will continue to thrive, and is now back in Kenya. ‘I’m talking with Kenyan Wildlife Services at the moment about a possible return to Kora. For the past 15 years, I’ve maintained George’s old camp. I brought a lion in again a few years ago, but I’ve never managed to kick-start it and get it off the ground.’

He’s already drawn up a possible 10-year plan, that includes building a rhino sanctuary, and is hopeful Covid-19 will not get in the way. ‘From what I’ve seen here, [the pandemic] was a big shock to everybody. But as far as the wild animals are concerned, if I can generalise, everything looks in pretty good shape. I haven’t heard of a massive increase in poaching anywhere. People have learnt to adapt, extra money has been raised, and everyone’s going to have to tighten their belts. It’s going to hurt in the long run, maybe, but I think people are learning to adapt, and the line is being held right now.’

Fitzjohn has always shunned any kind of praise for his extraordinary achievements. His hopes for the future are much the same as they have been all his life: to live in Africa, surrounded by wildlife, with more animals than people to speak to. And this time he knows exactly where he belongs. ‘My heart’s in Kora,’ he says simply. ‘It’s in my bones.’